What is Channel Management?

Channel management refers to the process a company uses to determine the best marketing techniques and sales channel strategies to reach the largest possible number of target customers. The “channel” is the indirect route, as opposed to the direct sales force, to market a B2B sales organization’s products and solutions to end customers.

The economics of selling through distributed channels are compelling:

- Benefits for manufacturers

A channel partner can help lower the cost of sales and service, extend reach, and help them target and service more attractive segments and pockets of demand. Effective channel management efforts also allow manufacturers to build stronger relationships with their partner network, facilitating better alignment with market conditions and increased sales revenues. - Benefits for customers

A distributor or channel partner can help lower acquisition and use costs while aggregating offers from multiple suppliers to deliver broader solutions – and often with improved service quality and dedicated support. In turn, this creates a better overall experience for customers and boosts customer satisfaction by providing tailored solutions that align with their needs.

There are compelling reasons, but manufacturers embarking on this process need to realize that the tools, marketing, and support needs of a channel are different than the resources they need to support their direct sales organization. Successful channel strategies must focus on maintaining clear lines of communication, understanding customer preferences, and using data-driven decisions to optimize performance. Before we get started on reviewing those differences, let’s review a few key terms.

Key Components of Channel Management

There are a few terms of channel management that should be defined:

- A manufacturer or supplier – starts the process by making and shipping the product. This entity plays a critical role in designing effective channel programs that align with their overall business goals.

- The distributor, wholesaler, marketer, VAR, ISV, or channel partner comes next, taking the title to the product and reselling it to end-users. This step offers logistics services, value-added services, and may “design-in” the suppliers’ products. They may also “break bulk” – buy in volume and sell in smaller quantities – or offer cross-brand bundles, blend solutions, or add services. Manufacturers call any entity in this group their “sold-to.”

- End-users or end-customers are the entities that ultimately use the product, and typically do not sell onward to another tier or customer. This is a channel partner’s “customer,” and understanding their needs is critical for optimizing both pricing strategies and overall satisfaction.

- A “ship to” can be the channel partner, end-user, subcontractor, or converter (in the process industry) that receives the products shipped by a manufacturer or supplier.

Manufacturers need to decide how they will engage commercially with the channel. Factors such as pricing structures, incentives for their partner network, and tools like channel management software play an essential role in building successful partnerships while minimizing risks like channel conflict.

Types of Channels

Businesses use different types of channels to distribute their products and services, each with its own advantages and challenges. Below is a clear breakdown of the main types of channels and how they function:

Direct Sales Channels

Direct sales channels involve selling directly to the end customer without intermediaries. This approach allows manufacturers to maintain full control over pricing, customer relationships, and market positioning. For example, many software companies use direct sales teams or e-commerce platforms to engage customers directly, ensuring maximum visibility into customer needs and preferences.

Indirect Sales Channels

Indirect channels rely on intermediaries such as distributors, resellers, or retailers to bring products to market. In this model, channel partners purchase inventory at a negotiated price and are responsible for managing commercial relationships with their customers. While this approach simplifies logistics for manufacturers, it can limit their ability to:

- Influence their products’ value position in the end-user market.

- Capture valuable market insights about customer preferences and product performance.

- Realize full revenue potential due to reliance on a single price or discount structure.

For example, the semiconductor industry often uses differentiated pricing strategies through indirect channels to maximize revenue while managing complexity.

Hybrid Channels

Hybrid channels combine direct and indirect approaches by allowing manufacturers to sell directly to some customers while leveraging intermediaries for others. For instance, a manufacturer might sell high-value, custom solutions directly to enterprise clients while using distributors for standard products in smaller markets. This model provides flexibility but requires careful management to avoid channel conflicts and ensure consistent pricing strategies.

Online Channels

The rise of e-commerce has created new opportunities for manufacturers to engage with customers digitally. Online channels include company-owned websites, third-party marketplaces (like Amazon or Alibaba), or distributor portals. These channels improve price realization by offering transparency and enable manufacturers to track end-use consumption more effectively through digital tools like analytics dashboards or CPQ software.

Value-Added Resellers (VARs)

Value-added resellers not only sell products but also enhance them with additional services like installation, customization, or ongoing support. This channel is common in industries like IT or industrial equipment, where expertise and service are critical differentiators. VARs help manufacturers reach niche markets while improving the perceived value of their offerings.

Why Channel Differentiation Matters

Each type of channel offers unique benefits depending on the business model and industry context. For example:

- Moving from a single discount structure to differentiated pricing through indirect channels can maximize revenue and value realization but adds complexity to the process.

- Supporting end-user price points allows suppliers to improve price realization, better understand their products’ market value, and track consumption patterns more effectively.

By adopting a mix of these channels and leveraging tools like Vendavo’s pricing solutions, businesses can optimize their go-to-market strategies while maintaining competitive positioning in today’s dynamic markets.

Channel Management Strategies and Examples

The way a manufacturer chooses to engage with the channel – and the type of partnership they want to establish – makes a difference. This decision has an impact on the entire commercial process, from financial and shipping terms to the type of relationship the manufacturer will have with their end customers and the type of tools and data required to manage the process. It is critical to understand these differences.

1. Tailoring Channel Strategies by Industry

Different industries require unique channel management approaches. For example:

- Automotive manufacturing: Companies use channel management platforms to coordinate with suppliers, dealerships, and service providers, ensuring timely delivery of parts and seamless customer experiences.

- Consumer electronics: Effective channel management ensures product availability across retailers, online marketplaces, and service centers while using automation to track sales performance and manage promotions.

- Energy production: By leveraging data analytics, energy companies optimize distribution networks and improve service quality through better coordination with distributors and contractors.

2. Leveraging Technology for Efficiency

Technology plays a central role in modern channel management. Automated platforms streamline communications, track partner performance, and provide real-time insights. For instance, manufacturers can use tools to monitor inventory levels, offer training to partners, or even automate rebate programs—all of which improve partner satisfaction and operational efficiency.

3. Driving Direct Sales Through Indirect Channels

Manufacturers often rely on indirect channels like distributors or external reps to access end-users. However, many are now investing in strategies to increase direct engagement with customers through these channels. For example, 75% of leading manufacturers still depend on indirect channels for significant revenue, but they are enhancing their influence by providing tailored marketing support or creating dedicated account management teams for strategic accounts.

4. Resolving Channel Conflicts with Pricing Strategies

Pricing alignment is critical to managing channel conflicts effectively. Brands like Harry’s harmonized prices across all channels to prevent competition between partners, while others like Beardbrand pivoted away from Amazon to focus on direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales, boosting revenue by over 20%. These examples highlight how strategic pricing decisions can strengthen relationships with channel partners while maximizing profitability.

5. Expanding Online Channels

The rise of e-commerce has pushed manufacturers to invest heavily in online sales channels. By offering self-service tools like product configurators or digital marketplaces, companies can cater to buyers who prefer digital-first interactions. This approach not only meets customer expectations but also reduces reliance on traditional field-based sales teams.

The Channel Management Process

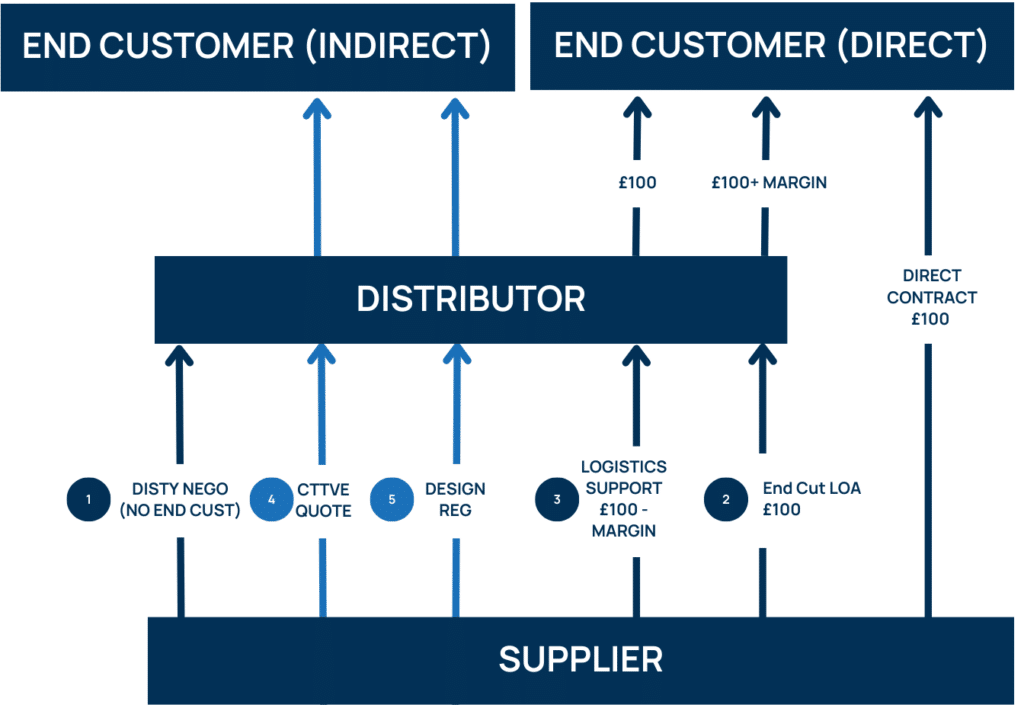

Distributors buy either at list or at a negotiated introductory stock price. The simplest version of a channel sales strategy is to sell to the partner and forget about what happens next. To really achieve value from the channel sale, suppliers must evaluate, track and manage “end-user supported” prices, which starts with a list price that reflects the product’s value and then a two-step process:

- Shipments to the distribution channel are invoiced at the list price or, in some cases, a negotiated “into stock” price.

- The second step is called different things in different industries, including “ship and debit,” or a “special pricing agreement (SPA),” “deviated price agreement (DPA or DPR),” or “end-user contract.”

Here’s what to know about some other common approaches:

Ship & debit

The process of differentiating the distributor’s buy price is typically covered under ship & debit. This is an agreed-upon discount paid out after the proof of sale (PoS), not a rebate. The distributor provides PoS data to prove the shipment went to the end customer, and the manufacturer pays the distributor a credit based on the PoS volume and agreed-upon discount. This approach ensures alignment between channel programs and market demand while minimizing channel conflict by maintaining transparency in pricing adjustments.

Metrics and analytics

Manufacturers who sell through distribution are aggressively trying to manage end-user pricing even if they don’t invoice the end-user. They need to analyze shipments, invoiced revenue, credits, historical weighted average support price and, if you can get it, end-user pricing.

- Price and margin waterfall – Building a price and margin waterfall needs to account for the different steps in the commercial process. For shipments to the distributor, invoice price = list price or into stock price. The end-user price will come from the PoS data. For direct shipments, invoice price = end-user supported price and equal to invoice price.

- Distributor margin – This may require separate reporting and a separate waterfall to capture this information. Whether estimated or calculated, the distributor’s margin is not a price point in the manufacturer’s waterfall. This kind of analysis requires the right price waterfall.

This distinction between the physical flow and financial flow of a transaction creates pricing, rebate, administrative, and analytical challenges for manufacturers. There is not always a direct correlation between the flows. Different use cases involve different waterfall elements, but in all cases, an end-user supported price point is a pricing best practice.

Channel Management Direct Ship Use Cases

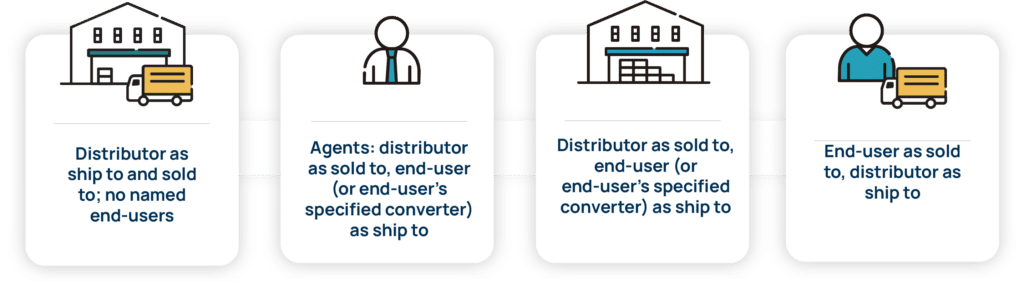

Many manufacturers sell through channel partners but ship directly to the end-user or to a converter upon the instructions of the end-user. Common direct-ship use cases include:

- Distributor as ship to and sold to; no named end-users

This treats the distributor as a customer, and is not a best practice. Sell to the distributor at price and ship to specified location of the end-user or converter. Often the manufacturer will have no visibility into the distributor’s resale price. - Agents: distributor as sold to, end-user (or end-user’s specified converter) as ship to

Sellers in all industries use agents, especially in Asia. Agents differ from distributors in that they generally do not take title of the goods. Their commissions must be considered as a service cost, like payment terms or rebates. Agents are neither ship to nor sold to, and in these transactions the end-user price is generally the invoice price. Agent commissions are a waterfall element beneath invoice price and above pocket price. - Distributor as sold to, end-user (or end-user’s specified converter) as ship to

In this case, the distributor but not shipment for a named end-user. In some industries, this use case is handled by billing the distributor with no visibility into the end-user price, but, more commonly, the supplier needs/desired visibility into the end-user price. The invoice price is assumed to be the end-user price, but the distributor is compensated with an on-invoice “trade discount” off the invoice price. One adds the on-invoice “trade discount” adjustment to the waterfall. - End-user as sold to, distributor as ship to

In many industries, sellers leverage distributors for logistics – particularly in servicing national accounts. In this scenario, manufacturers might negotiate directly with the end-user but use a distributor for stocking and delivery. The distributor takes delivery and is paid a “service fee” in return for logistics services. The waterfall element required here is “marketer service fee” or “logistics allowance,” falling between invoice price and net price.

Channel Management Indirect Ship Use Cases

Indirect ship use cases are most associated with selling through the channel. Here are a few facts to keep in mind:

- Distributors, marketers, resellers, and VARs add value by stocking, breaking bulk, and bundling other products and services to add value to manufacturer and end-user alike.

- Manufacturers employ distributors to help target attractive end-users and end-use segments.

- The benefit of leveraging distributors is increasing product and customer mix, targeting smaller end-users who should be paying higher prices.

Whether the distributor is billed at list or at a negotiated “into stock” price, the distributor asks for price support on selected end-user opportunities. The percentage of distributor sales that carries an additional discount will vary by industry and distributor. In cases where distributors take product into their warehouses and may break bulk, the end-user supported price point is a critical waterfall element and a best practice.

Here’s a common indirect-ship use case:

The distributor buys to hold in inventory, purchasing at either list price or a negotiated “into stock” price. It competes for business in the end market and receives compensation for shipments of the manufacturer’s products to indirect customers.

There is an impact on waterfall design including on the into stock price, end-user supported price, invoice price, and ship and debit adjustment.

A short word on rebates

Many manufacturers will have rebates, and a ship and debit discount (managed in a rebate system). Distributor and end-user rebates fall below end-user supported price and above net or pocket price in the waterfall, however. Effective rebate management offers a lot of benefits.

Benefits of Channel Management

There are clear benefits of selling through the channel, including:

- Lowering the cost of sales and support

- Selling to “smaller” customers that cannot justify the investment of a direct sales and support team

- Extending the ability to address geographical markets that would otherwise be out of reach for the manufacturer

- Helping manufacturers target more attractive segments and pockets of demand

- Gaining a broader understanding of the products’ market value by selling to a wider customer base

Challenges of Channel Management

There are a few legal questions that come up a lot. This is because manufacturers used to be able to dictate the resale price that the channel partner could offer. But this is now illegal, so don’t do it.

Legal issues come up when trying to set a minimum sale price, because resellers have the right to discount at their discretion. Many resellers will offer a recommended resale price (RSP) for products or services – provided it is a pure recommendation – and to set a maximum resale price.

Another common theme is that antitrust law mandates that supplier must quote the same end-user supported price to each authorized distributor who wants to quote on that deal, but this is not the case. Here is what to know:

- The design registration process in the semiconductor industry addresses this point and supports a process of differentiated pricing.

- A distributor registers a “claim” for the work they have done to design in a supplier’s chip. Approval of that registration gives them “protection” from another distributor selling to the same end customer.

- The “protection” means the distributor who has done all the work will get preferential buy-price pricing, while other interested distributors will have to quote using the list price.

A best practice channel pricing waterfall will improve both the efficiency and effectiveness of channel pricing decisions. The ability to analyze across the right price waterfall is required to support channel pricing best practices. Managing the channel and associated pricing processes is a complex business, but worth the effort to drive margin and mix positive growth, extending sales reach, and targeting smaller customers who will pay more without increasing sales and service costs or credit risk.

Synonyms for Channel Management

Channel management is a broad term with several related concepts and overlapping terminology. These synonyms reflect the various aspects of managing and optimizing sales and distribution channels:

- Channel optimization

- Channel strategy

- Distribution management

- Partner relationship management (PRM)

- Sales channel management

- Channel partner management

- Indirect sales management

- Channel sales strategy

- Multi-channel management

- Partner enablement

- Channel marketing strategy

- Go-to-market (GTM) strategy

- Distribution channel strategy

These terms highlight the multifaceted nature of channel management, encompassing everything from partner relationships to sales strategies and distribution logistics.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How can businesses optimize their channel management strategies?

Evaluate the different channel partner options and select the appropriate channel partnership to fit your overall commercial strategy. Do not treat the channel partners like second-class citizens. Understand the impact of selling through the channel and the consequences for your internal processes, marketing, and support.

How does channel management improve customer experience?

The supplier’s brand and positioning benefits from close relationships by enabling products to be sold, delivered, and supported by a partner of choice for the end-customer. The end-customer is happy dealing with fewer commercial partners. They can influence those relationships with higher buying power and ultimately get better service and support. Everyone wins.

How should suppliers manage volume pricing in the channel?

Volume-based pricing is a volume discount method used to reward or incentivize your channel partners to drive them to purchase in bulk amounts or in larger quantities. The discount can be based upon the quantity negotiated or ordered. Quantity can be measured in three ways:

- Target: the discount is based upon a negotiated quantity

- Step: the discount is based upon a quantity on a single order and reset at each order

- Scaled: the discount is based upon a cumulative quantity ordered over a set time period

The general principle is that discounts increase as the volume increases. More volume equals a higher discount. There is a fundamental assumption here that economies of scale apply, and total per unit costs go down as the volume increases.

What are the types of volume-tiered pricing that can be deployed in the channel?

These can be ordered into a hierarchy of benefits for the supplier, from good to the best option. These may all be applicable at different times, for different channel partners:

- Volume discounts

At the lowest end is the standard upfront volume discounts given to the customer with no contracted penalty for non-achievement of the volume

- This can work if you can at least track the volume compliance over time and warn sales early enough in the case of non-compliance.

- Disadvantages are clear, as the discount is given upfront there is no way to recover from that negotiation position.

- Volume-tiered contract pricing

This involves giving away more discount as the volume grows.

- The benefits back-end discounts granted based upon actual volume shipped.

- This can still lead to price erosion, as it is hard to raise price once reference established.

- Volume-driven guidelines

This reduces cycle time while increasing scrutiny on unwarranted discounts. This enables you to communicate pricing volume strategies to the sales force, signaling what is an “acceptable price.” This process is often employed where the focus it to improve sales force productivity.

- Volume-based rebates

This is the best option. It is granted based upon actual volume shipped, paid after the fact, and are the most secure (in terms of risk), accurate, and fair (in terms of reward for performance) form of volume-based pricing. These rebates also eliminate reference price points for products reaching the market, thus curbing future price erosion.