In this article, VP of Business Consulting, David Anderson covers a comprehensive overview of common types of rebates and use cases, tips for putting rebates to good use, and suggestions for avoiding the common commercial and administrative challenges rebates can pose.

In B2B pricing, rebates and incentives are a pricing best practice. Why? Because if you are not using customer rebates, you’re likely giving customers discounts they haven’t yet earned. Rebate manamagement programs ensure that delivered purchases directly drive net price paid, and that the complexities of managing rebate agreements do not outweigh the commercial benefits.

What Are Price Rebates and What Are They Used For?

Price rebates are retrospective financial incentives that return a portion of purchase costs to buyers after meeting specific conditions or performance targets. Unlike immediate discounts, rebates serve as a strategic pricing tool that protects initial price points while rewarding desired customer behaviors. Successful rebate programs leverage these incentives to align buyer actions with supplier goals, driving measurable outcomes like revenue growth and improved business performance.

Rebates are used to price on ‘actual’ rather than ‘promised’ purchases, instead of granting a discount upfront and accepting the responsibility to audit sales to the customer, or worse, not auditing, the seller grants a discount only for actual volume, thereby passing the risk of non-compliance to the buyer. This approach is especially effective in volume incentive rebates, where thresholds must be met before earning incentive.

In addition to pricing on actual rather than promised volumes, customer price rebates can be structured to drive specific customer behavior such as growth, retention, product mix improvement, or purchases of bundled offers. Like other forms of discounts employed to modify behavior, rebates allow sellers to communicate to customers how the customer receives the lowest price. The burden of realizing the lowest price falls on the customer, with the rebate granted only to achieve the specified outcome.

By automating these processes with rebate management software, businesses can reduce reliance on manual processes, streamline operations, and enhance customer satisfaction.

How Do Price Rebates Work

Price rebates function as retrospective financial incentives that return a portion of the purchase price to buyers after meeting specific conditions. Unlike immediate discounts, these payments occur post-purchase and typically follow a structured process of verification and settlement. Rebate management software can streamline this process, reducing errors and ensuring timely payouts.

A typical B2B rebate begins with a contractual agreement outlining specific eligibility conditions, such as purchase volumes or sales targets. The supplier tracks customer purchases through electronic data interchange (EDI) or similar systems to monitor progress. Once conditions are met, rebates are issued as checks, credit notes, or direct deposits. For businesses managing complex rebate agreements, automation tools can significantly improve efficiency and accuracy.

For example, a manufacturer might offer distributors a tiered rebate program where purchasing 10,000 units triggers a 4% retrospective rebate on all purchases during the contract period. This structure incentivizes higher purchase volumes while maintaining initial price points. Such volume incentive rebates encourage customers to increase their annual purchases, driving business growth for both parties.

The effectiveness of rebate programs relies on clear documentation, consistent tracking, and timely processing of claims. Modern rebate management systems help automate these processes, ensuring accurate calculation and distribution of rewards while maintaining program transparency. By eliminating reliance on manual processes, companies can focus on improving customer satisfaction and achieving measurable revenue growth.

Why Use a Customer Rebate Program?

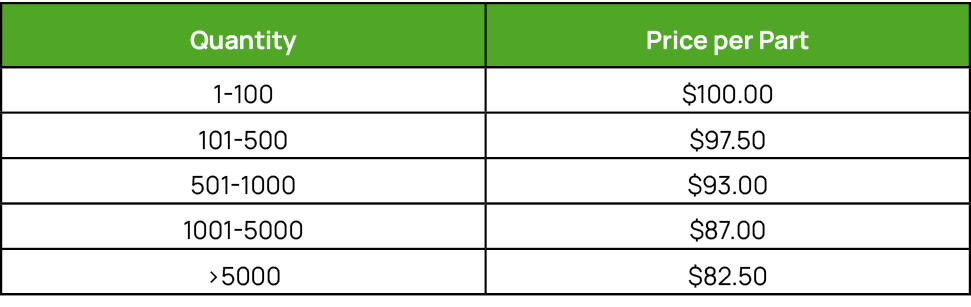

When quoting prices, many sellers in B2B consider the sales volume associated with the opportunity, deal, quote, or contract. For example, if a customer says they plan to buy 100 tons of LDPE (low-density polyethylene), the seller will quote a lower price per pound than if the opportunity is for only 22 tons. Or, similarly, 100 parts vs. 5,000 parts.

This practice, common across a number of industries, is called volume-based pricing or volume-based discount guidelines. The commercial rationale for the seller is that larger volumes create production, sales, and logistics efficiencies which can be passed on to the customer as larger discounts.

But what happens when the customer who promised to buy 100 tons only buys 22 tons? Or when a price quote for 5,000 parts generates an order that turns out to be only 800 parts?

In these situations of ‘over-promised volume,’ the seller probably cannot retroactively change the customer’s price. And, because the realized price does not comply with the volume sold, the customer has, in effect, extracted a noncompliant price. For Six Sigma practitioners, this is known as a defect. And, the defect has cost the seller money. A customer rebate program is employed to limit the gap between promised and actual behavior.

By tying discounts to actual performance through tools like rebate-per-unit structures or tiered incentives, sellers can protect margins while encouraging compliance with agreed-upon terms.

Rebates vs. Discounts

While both rebates and discounts serve as financial incentives, they differ significantly in their implementation and strategic value. Rebates function as post-purchase reimbursements, requiring customers to pay full price initially and receive money back after meeting specific conditions. Discounts, conversely, provide immediate price reductions at the point of sale.

Rebates offer distinct advantages in B2B environments. They help maintain price positioning while avoiding the negative quality associations that sometimes come with discounts. Additionally, rebates provide greater flexibility in year-over-year negotiations and serve as effective long-term sales strategies.

For example, rebate-per-unit structures or volume incentive rebates can encourage customers to increase their annual purchases, driving business growth while maintaining healthy margins.

| Feature | Discounts | Rebates |

| Timing | Immediate at purchase | Post-purchase reimbursement |

| Implementation | Simple, no paperwork | Requires proof of purchase |

| Duration | Often short-term | Typically long-term agreements |

| Price Impact | Direct price reduction | Maintains list price integrity |

Rebates are often more strategic than discounts, as they encourage long-term partnership commitments while protecting pricing structures. They also provide better control over customer behavior and help maintain stable price points in the market. With modern rebate management programs, businesses can align incentives with desired outcomes to improve both business performance and customer satisfaction.

Types of Rebates

Rebates can be categorized by business objective and customer type. They are employed to manage incentive programs to achieve business objectives and to improve the effectiveness of selling through distribution.

Price rebates are strategic financial tools that can be creatively applied to encourage target outcomes. Some of the most effective rebate types include:

- Incentive Rebates

- Channel Management Rebates

- Volume Rebates

- Value Rebates

- Growth Rebates

- Retention Rebates

- Mix Rebates

- Logistics Rebates

When properly structured and managed, rebate programs create win-win scenarios that align supplier goals with partner success while providing measurable returns on investment. Below we explore these types of rebates in-depth.

Incentive Rebates

Incentive rebates form the cornerstone of strategic B2B pricing programs, designed to influence purchasing behavior and strengthen business relationships. These performance-based rewards create a clear path to value for partners while helping suppliers achieve specific commercial objectives.

- Volume Rebate: Reward partners for reaching predetermined purchase thresholds within a specified period, typically offering increasing rebate percentages as volume targets are met.

- Growth Rebate: Focus on year-over-year expansion by establishing baseline performance metrics and rewarding partners for exceeding previous period results.

- Retention Rebate: Strengthen long-term partnerships by rewarding consistent purchasing behavior over extended periods, often including loyalty tiers that increase benefits based on relationship longevity.

- Mix Rebate: Encourage partners to maintain a balanced portfolio by rewarding specific product mix ratios or minimum purchase requirements across different categories.

Examples of Channel Management Rebates

Channel management rebates are strategic tools to support distribution networks and maintain competitive market positioning. These specialized programs help manufacturers protect margins while enabling channel partners to compete effectively in their respective markets.

- Ship and Debit Rebates: Allow distributors to sell at competitive market prices while maintaining margins through post-sale compensation, particularly useful in highly competitive markets.

- Indirect Customer Rebates: Enable manufacturers to incentivize end customers while maintaining relationships through distribution channels, ensuring price consistency across the network.

- Price Masking Rebate: Help protect sensitive pricing information by separating the visible price from actual cost, allowing for discrete market-specific pricing adjustments without revealing confidential terms.

Volume Rebates

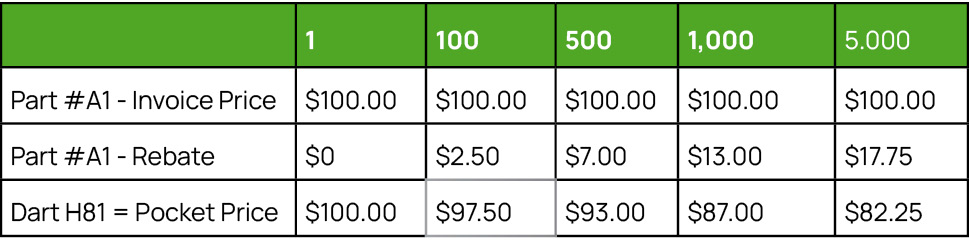

Volume rebates, a core aspect of rebate optimization, are the simplest rebate and are designed to limit customer gaming and over-promising. Instead of quoting a price-driven largely by the customer’s ‘intended’, or ‘promised’ volume, the seller responds with tiered pricing where the Invoice Price is fixed. Still, the actual price varies with volume, and the difference is granted by rebate.

Example:

In response to a customer inquiry, the seller quotes these volume/price combinations.

The example follows a simple story where:

- Quantity refers to the quantity of each order, rather than the cumulative quantity

- And the quoted price is not the invoice price, but the price, net of rebates

- In all cases, the supplier will invoice the customer at $100 per part

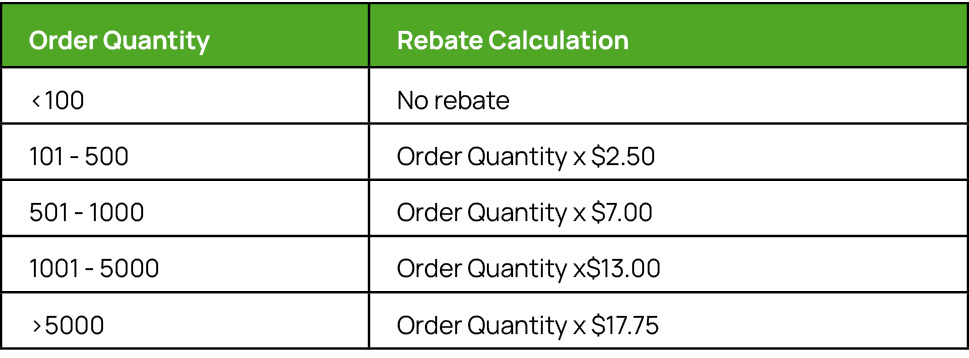

- The time period is calendar quarter

Then, at the end of the agreed time period, the supplier will measure the customer’s actual purchases and issue a volume rebate equivalent to the calculation based on volume depicted in the table below.

Value Rebates

Value rebates incentivize partners to focus on high-value product lines or strategic solutions that deliver greater profitability for both parties. Unlike volume-based programs that emphasize quantity, value rebates reward partners for selling specific products or maintaining certain price points that align with the supplier’s strategic objectives.

Here’s a simple example of how value rebates are implemented:

- Premium Product Line: 5% rebate on luxury or high-margin items

- Solution Bundles: 4% rebate when selling complete system packages

- Strategic Products: 3% rebate on new product launches or focus categories

Value rebates help suppliers maintain price positioning while encouraging partners to promote premium offerings. This approach protects brand value and market positioning while providing partners with stronger incentives to sell higher-margin products. The program structure typically rewards quality over quantity, helping organizations maintain profitability while avoiding excessive discounting on premium products.

Growth Rebates

Growth rebates are a simple variation of volume rebates, designed specifically to drive revenue growth or volume growth in a particular product family. Unlike traditional volume rebates, growth rebates focus on incremental gains rather than total revenue or volume. Here’s how they work.

Growth rebates reward customers for exceeding a baseline performance level (e.g., sales or purchase volume from a previous period). The rebate is paid only on the incremental volume above the established baseline, not on all revenue or total volume.

These rebates are particularly effective for:

- Launching new product lines

- Entering new markets

- Encouraging partners to actively pursue expansion opportunities

For example, imagine a supplier sets a baseline of 10,000 units sold in the prior year. If a distributor sells 12,000 units this year, the growth rebate applies only to the additional 2,000 units sold above the baseline. This structure motivates distributors to focus on increasing sales while controlling program costs for the supplier.

Retention Rebates

Retention rebates are designed to reward continued business and customer loyalty. These rebates encourage partners to maintain their purchasing commitments over time, fostering long-term relationships.

Retention rebates can take various forms—volume, mix, or growth rebates—but are typically structured as end-of-year or “cliff” rebates. The rebate is paid only when a specific condition is met, such as consistent purchasing behavior throughout the year.

As an example of a tiered retention rebate program, longer-term commitments are rewarded with higher rebate percentages, incentivizing relationship longevity. Interim milestone payments can be added to keep partners engaged and motivated throughout the year.

One of the greatest draws to retention rebates is making purchase patterns smoother. For partners with irregular buying habits, retention rebates provide financial motivation to normalize ordering cycles. This leads to:

- More predictable revenue streams for suppliers.

- Improved supply chain efficiency and better production planning.

- Enhanced inventory management for distributors.

By aligning incentives with consistent purchasing behavior, retention rebates strengthen partnerships and create a win-win scenario for both suppliers and their customers.

Mix Rebates

Mix rebates are a best practice for improving both the customer mix and product mix within a supply relationship. These rebates help sellers strategically guide distributors or customers toward higher-margin products or specific end-user segments. Mix rebates work by:

- Encouraging distributors to sell more volume of higher-margin or higher-value products.

- Incentivizing sales to selected end-users or target end-user segments that align with the seller’s goals.

Mix rebates are particularly effective when working with distributors or buying groups, as they help align their sales efforts with the seller’s priorities. While less common, mix rebates can also be applied to end-users to encourage specific purchasing behaviors in targeted segments.

As an integral part of the mix, variable rebate rates should rarely be a constant percentage (e.g., 2% on all revenue), as this risks being misinterpreted as a discount. Instead, sellers can apply different rebate rates to specific product families or customer segments, using rebates as a strategic lever to improve profitability and product mix.

The term “conditional rebate” refers to any rebate type tied to a set of conditions (e.g., minimum purchase thresholds or specific sales targets). When paired with conditions, mix rebates ensure that incentives are earned only when strategic objectives are met, maximizing their impact.

Logistics Rebates

Logistics rebates reward partners for behaviors that optimize supply chain efficiency and reduce operational costs. These programs incentivize practices such as full truckload orders, electronic ordering, or optimal delivery scheduling. By aligning financial rewards with operational efficiency, both suppliers and partners benefit from reduced handling costs and improved service levels.

Logistics rebates commonly target:

- Full Load Optimization: Additional 2-3% rebate for meeting full truckload requirements

- Digital Integration: Enhanced rates for partners using electronic ordering systems

- Delivery Scheduling: Premium rebates for accepting preferred delivery windows

- Container Utilization: Bonus incentives for maximizing shipping container capacity

These rebate programs prove particularly effective in industries with significant logistics costs, helping organizations optimize their distribution networks while providing partners with meaningful incentives for operational collaboration.

Rebate Program Examples

Effective rebate programs combine clear objectives with measurable outcomes to drive specific business behaviors. Understanding real-world applications helps organizations design programs that balance complexity with achievability while delivering meaningful value to all parties involved.

The following examples illustrate how different rebate structures can be implemented to address specific business challenges and market conditions.

- Volume rebate program: A beverage supplier offers a 3% rebate on purchases exceeding 20,000 units per month. This encourages distributors to place larger orders, helping the supplier increase sales volume while optimizing production schedules.

- Mix rebate program: A smartphone manufacturer provides a 5% rebate when distributors bundle smartphones with accessories like chargers or headphones. This incentivizes cross-selling and boosts sales of complementary products with higher profit margins.

- Ship & debit rebate: A distributor purchases roofing tiles from a manufacturer at $100 per case but needs to sell them at $90 per case to win a competitive bid for a large construction project. Through a Ship & Debit agreement, the manufacturer reimburses the distributor $10 per case after the sale, boosting profitability for both parties while enabling the distributor to secure the deal.

- Growth rebate program: A hardware supplier offers a 6% rebate if a distributor increases their purchases by 20% compared to the previous year. This motivates distributors to expand their sales efforts and drive incremental revenue growth for both parties.

- Retention rebate program: A chemical supplier rewards customers with a year-end 2% rebate if they maintain consistent monthly orders throughout the year. This smooths purchasing patterns, ensuring predictable revenue streams and fostering long-term loyalty.

These examples illustrate how targeted B2B rebate programs can align incentives with business objectives, creating win-win outcomes for suppliers and their customers.

“B2B rebate programs serve as strategic tools for vendors not only to boost sales but also to collect valuable data on customer purchasing patterns while reinforcing business relationships,” said Israel Rodrigo, Business Consultant at Vendavo. Read Israel’s related post: How to Set Up a B2B Rebate Program.

A Typical Example for a Ship & Debit Rebate

- Manufacturer sells to a stocking distributor

- Distributor buys roofing tiles from Manufacturer.

- Distributor buys to hold in inventory, purchasing at either List Price or a negotiated “Into Stock” price.

- Manufacturer invoices distributor at Into Stock Price of $100/case.

- Distributor competes for a specific large job: Cal Tech’s new Earthquake Center.

- Distributor calls Manufacturer for price support.

- The Cal Tech job is large, very competitive, and Distributor needs to match a competitive situation.

- The end-user price is $90/case, a price lower than the Distributors Into Stock Price.

- Distributor wins the Cal Tech job.

- And ships 200 cases of roofing tiles from their inventory to complete the job.

- Distributor files a Ship & Debit claim.

- 200 cases x [Into Stock Price – End-User Price].

- 200 cases x ($100 – $90)case = (200 x $10) = $2,000.

- Manufacturer pays a Ship & Debit rebate of $2,000 to Distributor.

In many cases, a manufacturer may have volume, mix, and growth rebates with the distributor, and have volume rebates with the end-user, and pay Ship & Debit claims on the same transactions. The net price for these sales would be calculated net of ALL price rebates.

Price Rebate Best Practices

Pay Rebates on Net or Pocket Price Points

In complex channel environments or when selling to large customers, a supplier may have multiple types of rebates on every transaction. The best practice is to pay rebates, not on invoice price but the pocket price.

- A supplier has monthly, quarterly and annual rebates with a “big box retailer” and pays a co-operative advertising discount of 2%. The supplier should pay the annual rebate on the price, the net of monthly and quarterly rebates, and net of the cooperative advertising, if possible. The dollar impact of the difference is significant.

- Another supplier has rebates for the distributor, end-user, and buying group. If possible, the buying group rebate should be paid on the end-user price and net of freight. This is not always commercially possible, but at the very least, the supplier should make this point as a begrudging concession during negotiation.

Indirect Customer Rebates

Indirect customer rebates, sometimes called end-user rebates, are rebates between a supplier and an indirect customer: that is, the seller never invoices this customer. Despite selling through the channel, the seller has visibility into major end-users, the supplier’s indirect customers, and wants to reward or motivate specific end-user behavior despite not having a credit or billing relationship with that customer.

Indirect customer rebates are an effective tool for maintaining a strategic supply relationship with an end-user, and driving price mix and volume objectives, despite the absence of a billing relationship. In most cases, indirect customer rebates take the form of a check, as opposed to a credit memo, which would be the case when a billing relationship exists. The servicing of “national accounts” often involves rebates of this kind.

Indirect customer rebates and Ship & Debit rebates often apply to the same transaction.

Price Masking Rebates

The other common driver of rebate use is the desire to keep the ‘real’ price visible in the market. Because a price rebate is, by definition, an off-invoice discount, the use of a price rebate allows the supplier to issue an invoice at a price that isn’t the actual, or net, price paid by the customer. Price Masking rebates, sometimes called shelter upcharges, are designed to allow invoicing at an artificially high price.

Price Masking rebates and shelter upcharges stem from a desire to avoid self-induced downward pricing pressure in competitive and transparent markets. In these situations, a supplier agrees to a price for a given customer but does not want to risk having that price become visible in the marketplace, believing, and rightfully so, that a price that low will cause market erosion. If other customers learn of that price, they too will want it.

Instead, the supplier invoices at a nominal price and then employs price rebates to bring the customer’s price down to the agreed net price. In this case, rebates are an effective method of quoting a low net price while invoicing at a higher price. The supplier recognizes that rumors of low net prices are one thing, but a low price on an invoice is the kind of evidence that can move markets.

Note: Price Masking rebates and shelter upcharges have been determined to be anticompetitive and illegal in some forms. Shelter upcharges are not a best practice, but you should understand the concept should they come up.

Similarly, when a corporate office does not want its regional offices to have visibility into true cost, the corporate office will often ask the supplier to issue all invoices at one price and then rebate the difference. National distributors frequently request this type of price rebate from their suppliers, effectively masking net price from their regional branches.

Avoiding any action that will create downward pricing pressure is a very good reason to employ rebates. But, if a supplier’s organization has trouble with the administration, management, or analysis of rebates, these tactical pricing options will be unavailable to them or more trouble than they are worth.

Whether you are using these types of price rebates to reward incremental volume, avoid customer gamesmanship or mask your true price on an invoice, rebates are a strategic and tactical pricing tool. Every element in the price waterfall of a business should, therefore, be for a specific purpose. This is especially true of rebates. If your business uses rebates, it should employ a set of rules for when rebates are applied, how they are evaluated, and a detailed definition of the process for applying them.

We’ll assume that if you are reading at this point, you do have rebates. The question for you then is: Are rebates helping you accomplish your stated pricing goals?

Structured Strategies for Price Rebates

Many organizations find themselves managing increasingly complex rebate structures that primarily drive one basic outcome: revenue. While technology has enabled more sophisticated programs, the fundamental question remains: Are these complexities delivering proportional value?

Evaluating Current Programs

Organizations should assess whether their rebates serve as strategic tools or have simply become an expected cost of doing business. Key questions to consider:

- Can program administration be simplified?

- Do you have a defined rebate strategy?

- Are programs regularly reviewed or automatically renewed?

- Does rebate complexity align with desired outcomes?

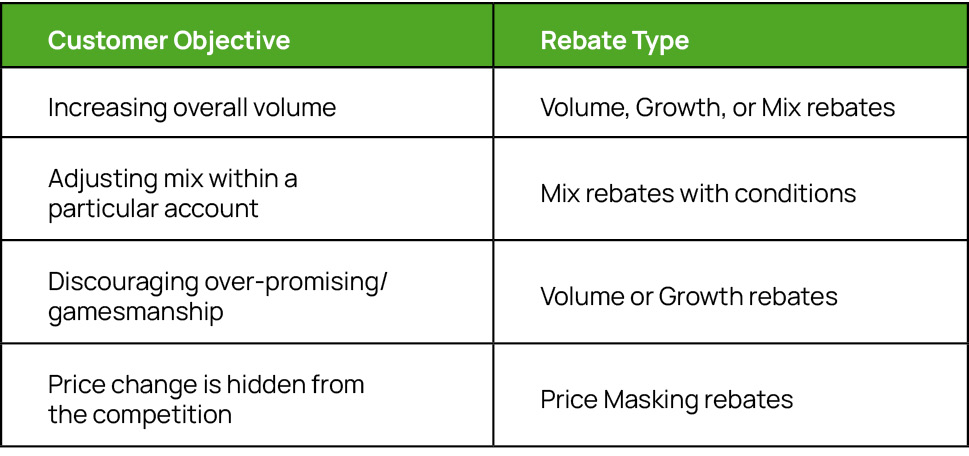

Developing a Strategic Approach

Start by establishing clear objectives for each channel, customer, or segment. Create a rebate playbook that matches specific customer behaviors with appropriate rebate types. This systematic approach helps:

- Reduce unnecessary complexity

- Ensure consistent application

- Match incentives to objectives

- Streamline administration

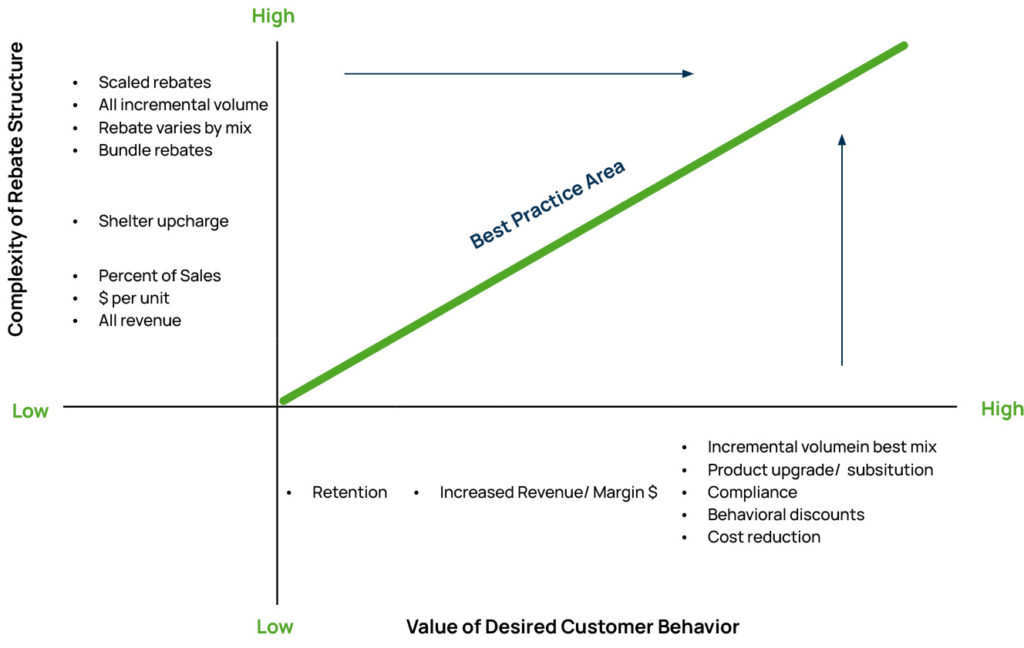

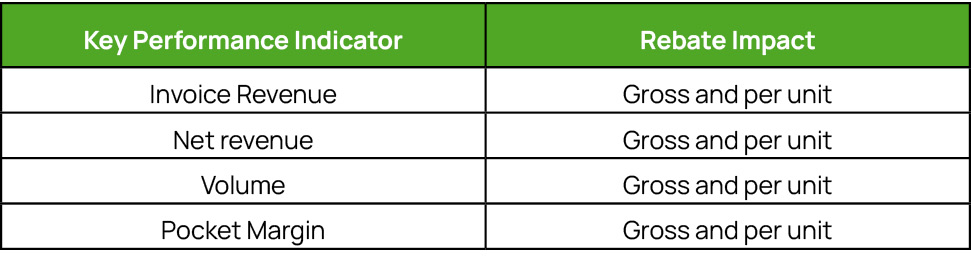

For example, rebate programs to help instruct your organization’s strategies, use the table below depicting common customer objectives and rebate structure types.

Balancing Complexity and Value

The most effective rebate programs operate within a “best practice band” where program complexity aligns with the value of desired customer behavior. Programs should be evaluated based on:

- Complexity of rebate structure (Low to High)

- Value of desired customer behavior (Low to High)

- Administrative costs versus behavioral impact

- Ability to track and manage effectively

The diagonal band represents the area of best practice. In the band, complex rebate structures foster specific and valuable customer behaviors. Such as gaining incremental volume in selected product families, and, thus, are considered best practice. Price rebates of low complexity are considered best practice when they achieve desired customer behavior.

Real World Challenges

Where possible, use rebates to accomplish your price realization objectives. But if that is not feasible, then increase your price efficiency by streamlining rebate mechanisms and processes.

Sounds simple, right? Maybe not. How hard can a volume rebate be to track and manage?

Aneesa Needel, Senior Product Marketing Manager at Vendavo, sums it up nicely: “To truly drive improvements, align your strategy with broader business goals, take on regular metric analysis, and leverage technology for tracking.” See Aneesa’s post on How to Measure and Grow Your Rebate Program for more.

Consider the semiconductor industry, where matrix pricing is common. Customer gaming and overpromising on volume commitments are endemic challenges. While rebates can effectively address these issues, many companies find them administratively burdensome. This highlights the critical need to balance program effectiveness with operational efficiency.

Implementation Considerations

When implementing rebate programs, organizations must weigh:

- Administrative costs and complexities

- System requirements for tracking and processing

- Internal resources needed for management

- Impact on pricing processes and workflows

The goal is to use rebates strategically where they deliver clear value while streamlining or eliminating programs that create unnecessary complexity without proportional returns.

Common Challenges Around Using Price Rebates

Quotation Visibility

Visibility into customer net pricing, net of rebates, at time of quote

Some rebates are annual, set up once a year, and apply to all volumes that meet rebate conditions. Suppose rebates are set up by management or maintained in spreadsheets or another system. In that case, the pricing desk and sales representative may be unaware of the existence of rebates at the time of quotation to a customer.

If you quote a price to a customer thinking it is a net price, and do not have visibility into the price net of rebate, you are experiencing price leakage.

When you match a competitive situation, and the competitor does not have a rebate, but you do, you are experiencing price leakage.

Analytical Visibility and Rebate Accounting Obligations

Visibility into actual customer profitability, net of customer rebates

After an order, suppliers working to analyze customer and product profitability turn first to invoice data. After extracting invoice data from a source system such as SAP BW, the pricing analyst loads variable cost data and endeavors to compare the margin contribution of all customer and product combinations.

But suppose if invoice price is the nominal price, before rebates where rebates exist, In that case, this waterfall analysis will be wrong or incomplete, and this customer will appear more profitable than it really is.

Clearly, price rebates need to be incorporated into any customer and profitability analysis. But often, this is easier said than done.

Access to Price Rebate Information

Many companies do not have a system of record for rebate information. Rebate information is often kept in a spreadsheet by one person. Rebate accruals are managed in yet another system. If the pricing analyst does not have access to this information, profitability reporting is wrong.

Handling Product Bundles

Rebate visibility can be even more complicated if the rebate is at the product bundle rather than the individual part level. How does a supplier allocate the rebate on a product bundle to individual parts when evaluating part profitability?

Sometimes reporting and accrual systems accrue rebates at the customer level only or the customer/product family level. How does the supplier allocate the rebate to an individual line item invoice level? Over time these questions may cause many suppliers to abandon rebates altogether.

Actual End-User Volumes

Often a manufacturer is utilizing an intermediary (distributor) to reach an end-user and employing a Ship & Debit rebate to set an end-user price. One or more distributors receive authorization for that end-user price in a multichannel environment, and the end-user may purchase through multiple channels. The manufacturer does not have full visibility to the distributors’ data, making it virtually impossible to track actual end-user volumes or volume rebate compliance.

This is especially true when several end customers can utilize the same product. This creates complexity in both administrating rebates and as customer compliance and win rates, etc. (multiple distributors/channels are quoting on the same business.)

Some companies have a decent success rate in demanding and receiving point of sale (POS) data from their distributors. This may reflect the balance of power in some industries, or POS incentive rebates in others.

Administration of Price Rebates

Also consider that revenue accounting rules require that rebates are tracked and accounted for properly and that financial statements reflect accurate income reporting given the impact of rebates on financials. It is thus a legal problem for a business to not fully understand and have controls in place to understand where rebate relationships exist, to properly accrue for the best estimate and impact of rebates in revenue reporting to the fullest extent possible at the time of a transaction.

Whether rebates are issued by credit memo or check, sellers and the financial team require a process for:

- Establishing rebate agreements

- Monitoring actual shipments vs. projected/forecast volumes

- Determining which shipments qualify for a rebate

- Calculating rebate

- Accruing for rebate

- Managing any rebate claims validation process with channel partners

- Issuing rebate check or credit memo

- Evaluating rebate for effectiveness

- Planning for next year’s rebate

The administration of rebates is often such a big problem that many companies chose not to employ them. For example, in recent research 60% of North American and 70% of European respondents admit rebate programs are costly and operationally challenging. In effect, these suppliers are choosing to sacrifice price effectiveness for price efficiency. Most suppliers understand that customers game them, would like to do something about it but view rebates as more trouble than they are worth.

The pricing best practice here is to substantially automate the rebate processes, removing all friction/variable costs from the rebate process so that a supplier can use rebates as a tool to increase price effectiveness and end customer gaming/overpromising.

Grandfathering

Even if a supplier has a process for issuing and allocating rebates, that supplier may fail to use the rebate tool effectively instead of allowing rebates to outlive their utility.

The problem, of course, is that rebates get rolled over from year to year without being closely inspected. Once established with a goal in mind, they quickly become expected by the customer and the sales representative. The seller is afraid to roll them back for fear of losing customer volume.

Rebates should be used to drive a very specific type of desired customer behavior. In the example above, the supplier wants the customer to buy more volume, and gives a price incentive to do so. By employing a rebate, the supplier makes sure that the customer only gets the price incentive if they actually buy the desired volume.

Significantly, with the price rebate mechanism in place, the burden for extracting this lowest price falls to the customer, not to the pricing desk.

Because rebates require an administrative effort to establish, most rebates apply not to spot opportunities but to ongoing supply arrangements between the supplier and ongoing trading partners, monthly customers or distributors. Rebates between regular trading partners are often established annually during a joint planning meeting.

If the seller cannot quantify the cost of a customer rebate program on an annual basis, or directly measure the impact of that rebate in relation to the behavior that they seek to encourage, then this is back in the category of rebate worst practices.

If sellers do not track these programs or quantify rebates accurately, they are also not compliant with revenue accounting rules and can be subject to penalties.

In Vendavo, with a ‘Rebate Performance Dashboard’ the seller can:

Track the impact of that rebate program along with a number of KPIs

Price Rebate Effectiveness

An incentive rebate is a discount like any other. A $1 invested in a rebate has an impact that can be quantified in volume, mix, or retention benefit. This can and should be quantified in a way that helps to compare rebate effectiveness.

Lump-Sum Payments

This document provides insight to types of rebates that are directly linked to one or more products, examples below:

- 1% on all revenue, means a 1 % rebate on all products

- 2% on product family A, 3% on product family B, similarly, can immediately be allocated to those product families

- $1.50 per part x is also easy to allocate

But what about rebates of this form?

I’ll give you, Mr. Distributor, $50,000 to help support your participation at the following trade show (at which you will represent my products)

From the perspective of waterfall construction, this $50,000, while certainly an off-invoice discount, is not a rebate. This kind of co-marketing expense would be reflected in another, non-rebate, waterfall element. The allocation of these kinds of ‘slush fund’ programs is non-trivial, and is dealt with in another document.

Waterfall Element Sensitivity

There are different types of rebates, employed for different tactical pricing objectives. In addition, there are different kinds of buyers. Some buyers seek to lower their ‘price,’ the invoice price per unit; other buyers seek to maximize their rebate checks, or the growth of their sales rebate payments year over year.

Over time, Vendavo can help sellers interpret their transactional data, telling the sellers which customers and segments appear to be very sensitive to invoice pricing changes, which appear to be more sensitive to changes in rebates.

This kind of information can help you increase prices more effectively. Increasing invoice prices to customers most sensitive to changes in rebates, and decreasing rebates to customers most sensitive to changes in invoice pricing.

Drive Customer Behavior and Avoid Price Leakage with Price Rebates

Rebates are a pricing best practice for driving specific customer behavior and avoiding price leakage. Define a sales rebate management strategy, pick the appropriate rebate, and manage execution tightly, measuring to ensure that they are accomplishing the intended goal.

Uniquely, Vendavo has capabilities that span commercial process, price setting, analytics, and rebate accounting execution. If you are interested in expanding the use of rebates in your pricing strategy, or are simply looking for more controls and visibility of rebates in your commercial or revenue accounting processes, give us a call.